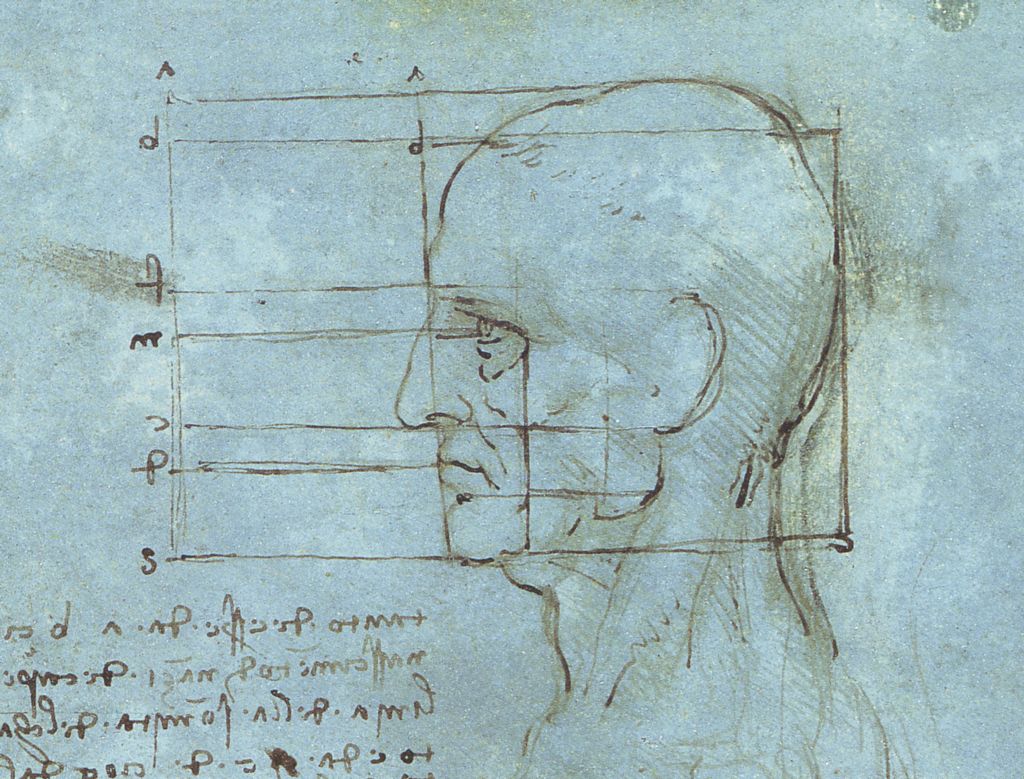

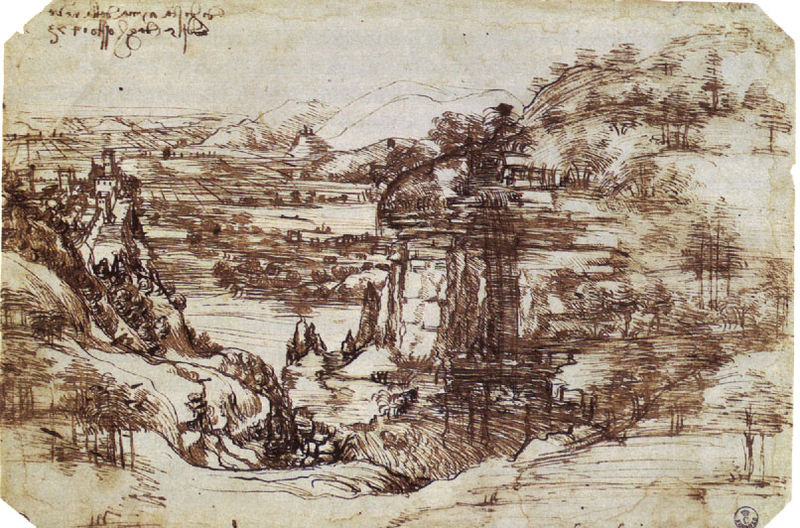

Although scholars in different parts of Europe had been studying ancient texts from Greek, Latin and Arabic since at least the 12th century, there was a flurry of translation and ‘re-discovery’ of lost texts in Italy in the 14th and early 15th centuries. This work was carried out by of learned men known as humanists on account of their wish to promote the study of the humanities and moral philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle. Even though they were devout Christians, they placed man, God’s supreme creation, at the centre of the Universe, responsible for his own actions and measure of all things. This, and growing interest in naturalistic depiction, led to a new emphasis on drawing human figures and demonstrating man’s potential to imitate, and even improve upon, nature.

Professor Catherine Whistler, Keeper of Western Art, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.