EARLY NUDES

Interest in the naked figure took different forms. From mid-fifteenth century on, all Italian apprentices were made to do regular drawings of the male body from life and two-and three-dimensional models. Leonardo advocated that on winter evenings, young artists should study all the nudes they had drawn in summer - when it was warm enough for their subjects to stand naked - correcting their efforts during the following year. The practice of drawing the female nude in Italy seems to have started much later, well after the turn of the 16th century.

This drawing, attributed to the Florentine Maso Finiguerra, is evidence that young artists practiced drawing models in a variety of poses. This type of drawing would become more common from the 1470s onwards.

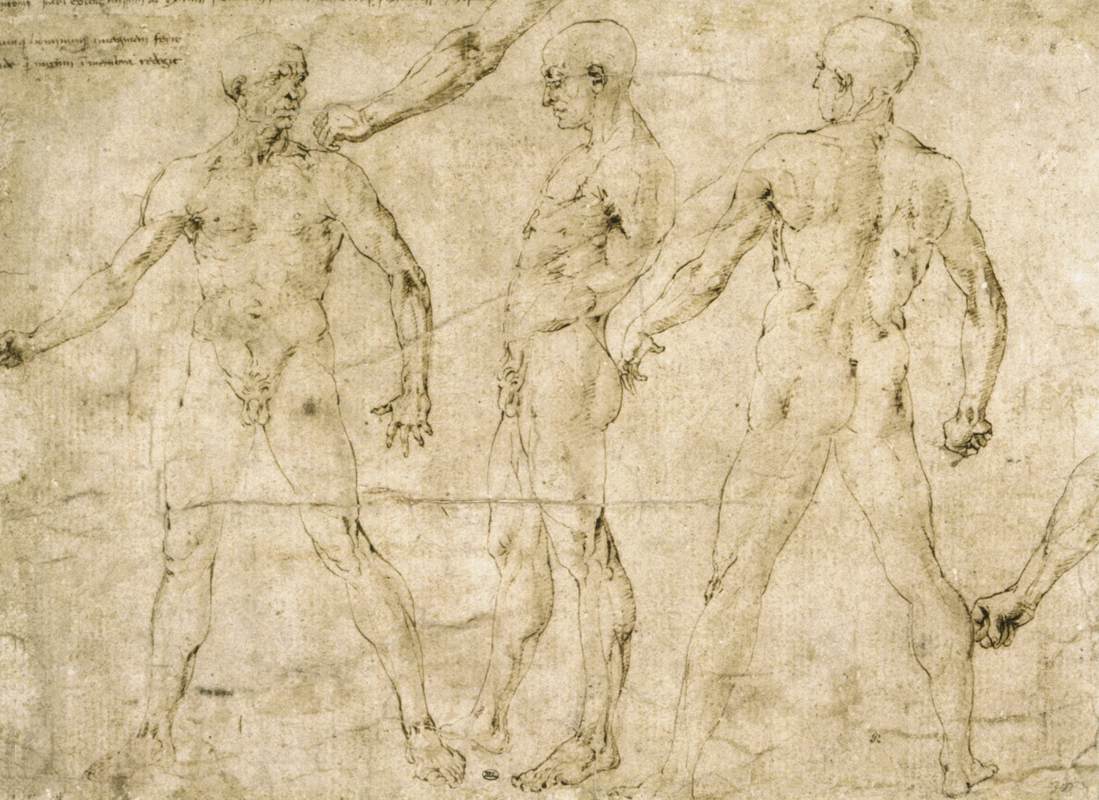

Pollaiuolo’s sculptural drawings of male nudes were copied by artists all over Europe. This one presents three views of an archetypal body which could be used to assemble the perfect whole.

The pose of Saint Sebastian, his sculptural form, and the winding path behind him derive from a painting of same subject by Mantegna who exercised considerable influence on many younger artists in this period.

Giovanni was the Venetian brother-in-law of Mantegna. He made many drawings of the Lamentation; in this one, strongly defined hatching is used not only to create deep shadows modelling the central figures but also to heighten the pathos and drama of the subject.

It wasn’t until the the early 16th century that studies of naked female bodies began to be produced. Even then, they were probably made to get accurate depictions for specific works rather than as part of the study of the ideal human body which was associated only with the male nude.

NORTHERN NUDES

Whether or not 15th-century northern European artists and apprentices did life-drawing exercises like their Italian contemporaries is not documented. Nevertheless, naked or semi-naked figures appear in early drawings by French and Flemish illuminators and artists such as the Master of the Cité des Dames (active from around 1405 to 1415) and Hugo van der Goes (ca. 1430-1482). The Study of a Naked Woman by Albecht Dürer (1471-1528), produced before he visited Italy, is perhaps the earliest surviving female nude drawn from life. He would return to the genre often: his expressive Nude Self Portrait is from after his second trip to Italy, as are his Four Books on Human Proportion based on the works of Vitruvius and Alberti. His most talented pupil, Hans Baldung Grien (ca. 1484-1545), also drew the nude from life.

Dürer’s apparently-naturalistic study of his own body here is remarkable in the context of his other nude drawings from the same period which depict ideal bodies influenced by classical sculpture.

In about 1512, Dürer decided to write a scientific treatise on human proportion which interested him for many years. This drawing, which served as the model for an illustration, is based on ideal proportions as defined by Vitruvius.

AFTER THE ANTIQUE

According to Alberti’s Della Pittura, the role of the arts is to create beauty by selecting the most “excellent parts… from the most beautiful bodies”. Young artists found these in classical sculptures which provided them with models for representing volume, pose and expression. Often they would copy these sculptures from drawings by their masters of monuments such as Marcus Aurelius and the Spinario in Rome, or from small three-dimensional models and casts. Nevertheless, with a few exceptions such as Mantegna, most artists took several decades to grasp the anatomical and formal principles of the originals. It was not until the following generation, that of Michelangelo (1475–1564) and Raphael (1483–1520), that artists would fully take on the challenge of representing the Antique. By then, Pope Julius II had filled the Vatican’s Belvedere Courtyard with newly excavated works such as the Hellenistic Laocöon, and Baccio Bandinelli (1488-1560) had started an informal academy in which the study of classical sculpture was a central part of the curriculum. This would be followed, some 30 years later, by the first formal academy, the Florentine Accademia del Disegno, established by Duke Cosimo de’Medici on the initiative of the artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574).

Pisanello must have seen this statue on a visit to Rome where it remained, on the Quirinal Hill near the Horse Tamers, throughout the Middle Ages. In the 15th century it was thought to represent Saturn.

Here the live model has been posed like the famous Greco-Roman sculpture of the Spinario, a practice which would become widespread in later centuries.

This drawing was probably drawn by Leonardo during his seven-year apprenticeship to Verrocchio who was then the leading sculptor in Florence.

This drawing reflects Dürer's admiration for antique sculpture – in particular, the Apollo Belvedere, which had been recently discovered and was considered the supreme example of male beauty. Although Dürer did not travel to Rome, it was known to him through drawings and was a source of inspiration in his search for the perfect anatomy.

The celebrated sculptor Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560) saw himself as Michelangelo’s rival, and in this work he is depicted as a man of learning, surrounded by books and antiquities and wearing a knight’s badge. One of his achievements was to secure from Pope Leo X (r. 1513-21) space in the Belvedere Courtyard at the Vatican for young artists to draw small models of Rome’s classical sculptures.

Dr Adriano Aymonino, University of Buckingham.